‘Mind Shift: confronting a colonial collection’ eloquently exposes the University of Edinburgh’s contributions to Phrenology and the role it played in 19th century scientific racism. Mind Shift ‘confronts’ the collection by examining its vast number of skulls, skull casts, and busts in tandem with the phrenological research being performed in Edinburgh.

‘Phrenology’ is the now discredited science of measuring the grooves and patterns of the skull in order to determine character, intelligence, aptitude, etc. Though it was never formally taught as an academic subject at the University, the city of Edinburgh was the centre of Phrenology in the 1800s with some of the University’s graduates contributed to establishing it as a field. Among them, Edinburgh University graduate George Combe who founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society; University Principal and Professor of Anatomy Sir William Turner who moved the phrenological collections to the Medical School on Teviot place; and Charles Darwin who participated in phrenological debates as a student and noted in the same notebook that would be used for his theories about natural selection: ‘one is tempted to believe phrenologists are right about habitual exercise of the mind altering form of the head, & thus these qualities become quite hereditary.’ (The M Notebook, 1838). The exhibition highlights how these figures lent this pseudoscience undue prestige and legitimacy.

In the 19th century Phrenology excluded Black people from narratives of civilization and progress by attributing superior capabilities to White people and inferior ones to Black people. This racist narrative provided a scientific basis for the civilising mission of the British colonies. Phrenology was not limited to Britain but also spread to the United States where anti-abolitionist thinkers employed phrenological justifications for slavery.

The exhibition also highlights the important contributions of 19th century contemporaries who worked to challenge these views. Frederick Douglass actively spoke out against Phrenology, exposing it as a discipline concerned exclusively in perpetuating slavery. Douglass said, ‘by making the enslaved a character fit only for slavery, they [phrenologists] excuse themselves for refusing to make the slave a free man.’ The exhibition also highlights the work of the lesser known James Beale Horton, the University’s first African graduate, who challenged the work of phrenologist and anti-abolitionist James Hunt, arguing that his work was founded on prejudicial views of men. Mind Shift pays due recognition to the scholars who were active in disputing the pseudoscience of Phrenology and does not attempt to claim that its proponents were merely ‘a product of their time’ nor ignorant to contending research in their field.

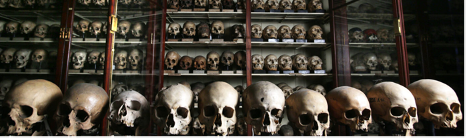

The exhibition then turns to an examination of the objects of the collection itself, highlighting that not only were the findings of Phrenology part of a colonial agenda, but also that the acquisition of the skulls themselves were only possible as a result of colonial coercion. Many of the 1800 skulls in the collection were actively stolen from overseas colonies. The exhibition contains an interactive map of Africa, drawing attention to various stories of people whose remains were stolen across various parts of the continent.

Turning to the present day, the exhibition demonstrates how some of the skulls in the collection have been used by the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification at the University of Dundee, where students have used the skulls for facial reconstruction projects that produce renderings of historical figures such as Pepe el Mallorquin, the notorious ‘last pirate of the Caribbean.’

In addition to archaeological studies and facial reconstruction, the University has been repatriating the skulls. Recently, Wanniya Uruwarige, Chief of Vedda in Sri Lanka, met with Principal Peter Mathieson to receive nine Vedda skulls taken from Sri Lanka in the 1880s.

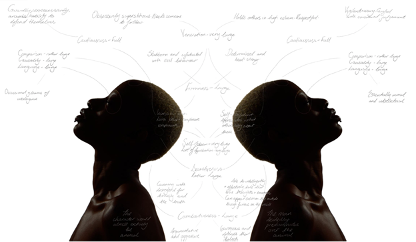

The exhibition concludes with Tayo Adekunle’s Fitting the Character, a mixed media photograph completed this year. Adekunle graduated from the Edinburgh College of Art in 2020 and has been working as a visual artist and photographer in London. Fitting the Character aims to apply the phrenological blueprint to her photograph, highlighting the bias implicit in phrenological language and the prejudicial difference between how it is used to describe white men and how it is used to describe Black people.

The exhibition states, ‘This exhibition spotlights the work of academics, curators, students and artists to uncover and confront this colonial collection over the past decade, but this work is incomplete. New projects continue to dig deeper to understand the impact of phrenology in Edinburgh and abroad, and its lingering influence in other racial sciences.’ Mind Shift’s careful curation captures the colonial heritage of the University’s collections and its contribution to phrenological studies and scientific racism. However, the exhibition is only part of the picture and there is still more work to be done.

Nonetheless, Mind Shift ought to serve as a model for other disciplines within the University interested in ‘decolonizing’. An exhibition of this nature could apply to subjects ranging from Philosophy (looking at the philosophic racism Hume) to Economics (examining Adam Smith’s descriptions of ‘savage’ people in Wealth of Nations). Edinburgh and the University are complicit in academic racism and, taking after Mind Shift, ought to consider further projects in ‘confronting’ its past.

To find out more and explore the online exhibition, please click here.

Written by Carley Wooten.